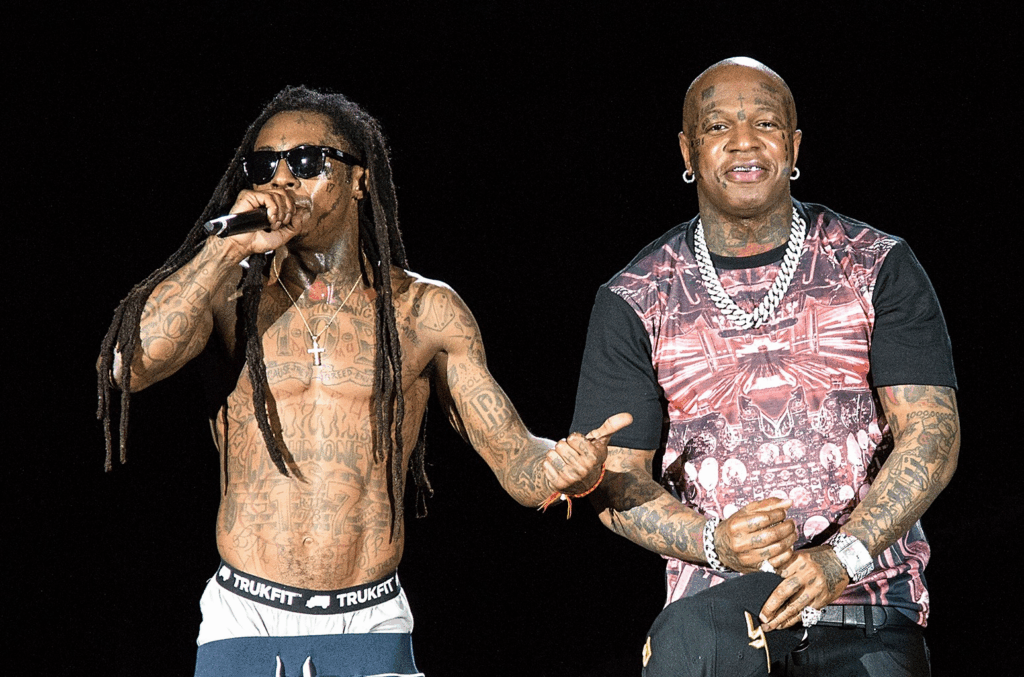

gs. Birdman was recently revealed to still hold about 20% of the royalties from Lil Wayne’s hit songs, even after their split and Wayne’s departure from Cash Money Records. Despite their past legal battles, Birdman continues to earn millions annually from Wayne’s catalog, highlighting how powerful music ownership and master rights remain long after an artist leaves a label.

The Background: A Father-Son Rap Empire

Birdman and Lil Wayne’s story begins in New Orleans, where Birdman, along with his brother Slim, founded Cash Money Records. Lil Wayne signed at a young age and would eventually become one of the label’s flagship artists. The relationship was often publicly framed in familial terms – Wayne often referred to Birdman as a father figure and Birdman as his “dad.” Over the years, the two collaborated both commercially and musically.

Cash Money’s roster during Wayne’s tenure included other megastars like Drake and Nicki Minaj, and the label achieved massive success. According to Birdman himself, the label has generated tens of millions of dollars annually from its masters. theshaderoom.com+3Black Enterprise+3hiphopwired.com+3 One recent article even quoted Birdman saying that the trio (Wayne, Drake, Minaj) had brought in over two billion dollars to Cash Money.

The Contractual Rift: Royalties, Ownership, and Departure

Despite the closeness of the relationship in public view, things began to sour behind the scenes. Lil Wayne filed a lawsuit in 2015 against Cash Money for approximately $51 million, alleging breach of contract and withholding of royalties. The dispute centered on his long-awaited album Tha Carter V and the financial terms he believed he was entitled to. Over time, the two sides negotiated, and Wayne left the label in 2018, under a settlement.

One important piece of that settlement: Wayne’s imprint, Young Money Entertainment, was transferred out of the Cash Money umbrella, and some ownership interests changed hands. While the exact percentage retained by Birdman or Cash Money for Wayne’s catalog is not explicitly detailed in publicly-available documents as “20 %,” the fact remains that Birdman and Cash Money continue to profit from masters and catalogs tied to past contracts.

Birdman admitted on the record that Cash Money generates between $20 million and $30 million a year just from their masters.That fact underscores the value of ownership and control over recording masters (and associated royalties) long after an artist has departed a label.

What It Means to “Still Hold Royalties”

When one says that Birdman still holds “20 %” of the royalties of Wayne’s hits, what does that actually mean in practical terms? Here are some key points:

- Masters vs Publishing: The “master” is the original recorded performance. If a label owns the master, then licensing for film, TV, streaming, samples, and other uses often pays to the owner of the master. Wayne reportedly sold his masters for a large amount in recent years. Meanwhile, Birdman has admitted that he licenses music, allows sampling, and is making millions every year from those catalogues.

- Royalties: Royalties flow from streams, sales, radio play, sync‐licensing, etc. Even if an artist leaves a label, the label may still be contractually entitled to a percentage of revenue from recordings made under the contract.

- Ownership Stakes & Percentage Deals: If Birdman retained (or negotiated to retain) a stake in Wayne’s catalog—say 20 %—then he would receive 20 % of certain royalty streams tied to those recordings. Whether that exact percentage is accurate depends on contract terms which are not fully public.

- Departure Doesn’t Always Equal Financial Clean Break: Even though Wayne has officially departed and is presumably operating independently, the legacy recordings produced while under label contract typically still result in ongoing revenue for the label unless contractually severed.

Therefore, the statement that Birdman “still holds 20 % of the royalties” is plausible in the sense that he and his label continue to benefit financially from Wayne’s earlier work, even though Wayne is no longer on Cash Money.

Why This Matters: Artist Rights & Industry Power

The situation draws attention to major issues in the music industry:

- Long-tail revenue & catalog value: Birdman’s claim of $20-30 million per year from masters highlights how revenue doesn’t stop when an album drops—it can generate income for decades via streaming, licensing, sampling.

- Artist vs Label leverage: An artist may leave a label or move on, but unless their contract specifically dictates they retain full ownership of masters and royalty streams, the label retains power and ongoing financial benefit.

- Negotiation & exit terms matter: In Wayne’s case, although he left the label, the legacy contract still appears to yield revenue for his former label partner. That underscores why artists endeavour to negotiate ownership of masters or favourable reversion clauses.

- Transparency & legal risk: The disputes between Wayne and Cash Money show how opaque contracts and accounting can lead to high‐stakes litigation. For example, Wayne claimed millions were owed to him.

Birdman’s Position & Perspective

From Birdman’s own statements, he views the ownership of masters as a key asset. He reportedly said:

“We license the music… I just started letting people sample my shit. So yeah, it’s a gang of ways you can make money with your masters. We generate $20-30 million a year just on our masters.”

This statement suggests two things: first, Birdman considers the catalog of recordings—including those made with Lil Wayne—as ongoing revenue streams; second, that controlling a piece of the royalty or master ownership translates into long‐term wealth.

When you couple that with his claim that Drake, Wayne and Nicki have generated over two billion dollars for Cash Money, the scale becomes clearer. The key takeaway: even after an artist leaves, if the label retains master rights or royalty stakes, they continue to benefit financially.

The Artist’s View – Lil Wayne’s Stakes & Legacy

Lil Wayne is widely considered one of the greatest rappers of his era. His early rise through Cash Money and Young Money helped shape hip-hop. He expected that success to translate to corresponding compensation and ownership. That expectation was partly behind the legal disputes.

Although he left the label and later sold parts of his catalog, the legacy recordings he made under the earlier label arrangement remain a complex asset. If Birdman holds 20 % of certain royalty streams tied to Wayne’s hits, then Wayne’s past success continues to deliver income to his former mentor/label partner.

For Wayne, the implications are that while he has more freedom now, part of the upside from his earlier era is still tied to a partner he has litigated against. That dynamic presents both financial and emotional consequences.

The Broader Implications for the Music Business

This case illustrates broader industry lessons:

- Master Ownership Matters: Many artists now publicly emphasise owning their masters to avoid the situation where their label (or former label) can earn decades of revenue beyond the artist’s control.

- Legacy Catalogs Are Gold Mines: As streaming continues, older recordings maintain value, particularly if they become part of film/TV placements or are sampled by new artists.

- Label/Artist Departures Aren’t Clean Slates: Even when an artist exits a label, prior agreements often continue to yield revenue for the label. Thus, contracts should specify reversion rights or termination of royalty obligations where possible.

- Artist Empowerment & Contract Literacy: Cases like Wayne/Birdman highlight why artists should have legal and financial advisors to understand the long-term implications of what may initially seem like favourable label deals.