qq “Those who compare Trump to Satan are wrong… because he’s even worse.”

When Politics Becomes Demonization Instead of Debate

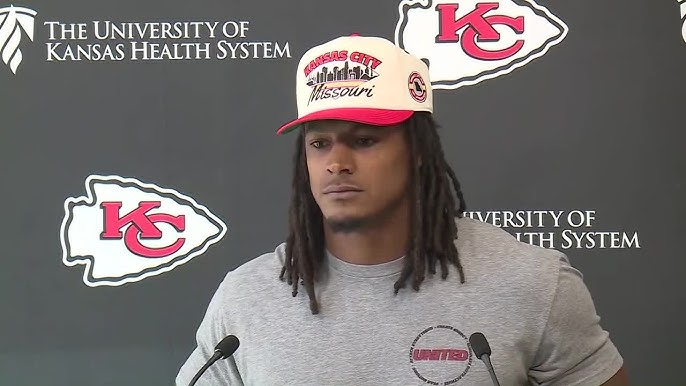

In a recent comment that quickly circulated online, NFL running back Isiah Pacheco reportedly said that people comparing former President Donald Trump to Satan were wrong — because, in his view, Trump was worse.

Whether meant as hyperbole, frustration, or provocation, the remark reflects something deeper about the current state of American political discourse. We are no longer arguing primarily about policy. We are no longer debating ideas, trade-offs, or competing visions for the country. Instead, we are witnessing a politics increasingly defined by moral condemnation, shock value, and public shaming.

From Disagreement to Demonization

Political disagreement is normal in a democracy. In fact, it is healthy. Citizens should argue passionately about taxation, immigration, healthcare, education, national security, and the role of government. Democracies thrive when competing ideas are tested openly.

But there is a meaningful difference between criticizing policies and condemning people as inherently evil.

When public figures — especially celebrities with large platforms — describe political opponents not as misguided, but as demonic or worse, the conversation shifts. It moves from persuasion to vilification. Once someone is framed as evil incarnate, dialogue becomes pointless. After all, you don’t negotiate with evil; you defeat it.

That framing changes everything.

The Power — and Responsibility — of Celebrity Voices

Athletes and entertainers have every right to express political opinions. Free speech does not belong exclusively to politicians or commentators. In modern culture, sports figures, musicians, and actors wield enormous influence. Their words carry weight far beyond locker rooms or stages.

But influence brings responsibility.

When a celebrity reduces a political figure — and by extension, millions of voters — to something worse than Satan, it is not merely a personal opinion. It becomes a cultural signal. It tells supporters that their views are not just mistaken but morally corrupt. And it tells opponents that outrage is the appropriate response.

The result is predictable: applause from one side, fury from the other, and a widening gap between them.

What Happens to Unity?

Calls for national unity have become almost ritualistic in American politics. After elections, after crises, after moments of violence, leaders urge citizens to come together. Yet unity cannot coexist with constant moral absolutism.

If half the country is portrayed as aligned with evil, why would they feel any obligation to engage in good faith? If voters feel demonized, they retreat further into defensive identity politics. The cycle intensifies: condemnation breeds resentment; resentment breeds counter-condemnation.

Soon, disagreement is no longer about policy outcomes but about personal virtue.

The Incentive Structure of Outrage

It is also worth acknowledging the role of media and social platforms. Provocative statements spread faster than nuanced arguments. Outrage generates clicks. Hyperbole travels further than moderation. In this environment, a sharp, shocking remark is often rewarded with attention — even if it deepens division.

The incentives do not favor calm, reasoned debate. They favor escalation.

And escalation is exactly what we are getting.

Can We Return to Substance?

The deeper question is not about one athlete or one former president. It is about whether American political culture can re-center itself around ideas rather than identities.

Can we argue fiercely about border policy without assuming malicious intent?

Can we criticize leadership decisions without dehumanizing supporters?

Can public figures express strong disagreement without resorting to apocalyptic language?

Democracy does not require agreement. It requires a shared belief that our opponents are still fellow citizens — not enemies to be destroyed.

A Choice Going Forward

Every public voice contributes to the tone of the national conversation. Politicians do. Media figures do. Celebrities do. And so do ordinary citizens online.

The question is not whether criticism should be sharp. It often should be. The question is whether it should be dehumanizing.

If the goal is persuasion, demonization rarely works. If the goal is unity, it is counterproductive. If the goal is attention, however, it may be wildly successful.

The direction of political discourse ultimately depends on what we reward — substance or spectacle, argument or outrage.

In the end, democracy is not weakened by disagreement. It is weakened when disagreement turns into dehumanization.