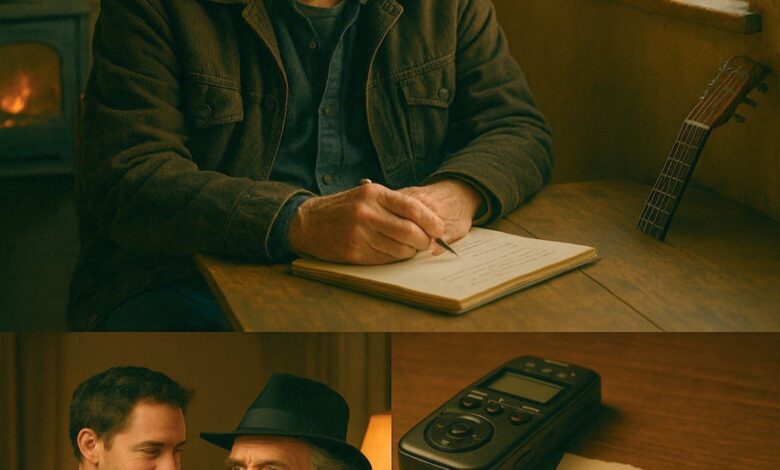

ST.“THE SONG HE COULDN’T FINISH UNTIL LIFE FINISHED IT FOR HIM.” Late in the winter of 2014, Merle was sitting in his small writing room behind the house in Palo Cedro. A heater hummed in the corner, and his old guitar leaned on the desk like it had been waiting all morning. He had a melody in his head — a slow, wandering tune that felt like footsteps in the snow. He tried writing the words, but every time he reached the second verse, he stopped. “Too close to home,” he told a friend. For months, he returned to that half-finished lyric. Then, one night, after a long talk with one of his sons, he picked up the guitar again. His voice was rougher, softer, but something had settled inside him. The song finally came out — not perfect, not polished, but honest in a way only time could shape. He never performed it on stage. He only played it twice in his living room. After his passing, his family found the demo on a small recorder, labeled in Merle’s handwriting: “Finish this when I’m gone.”

Late in the winter of 2014, Merle Haggard was spending most of his days in the small writing room behind his home in Palo Cedro. It wasn’t fancy — wood panel walls, a humming heater, and an old guitar resting on the desk like a loyal dog waiting for its owner. That tiny room had seen decades of melodies, heartbreaks, and quiet confessions. But that winter, something different lingered in the air.

He had a melody stuck in his mind — slow, wandering, gentle enough to sound like footsteps in fresh snow. Every time he tried to write the words, they stopped at the same place: the second verse. He told a close friend, “It’s too close to home.”

He wasn’t talking about difficulty.

He was talking about truth — the kind that hurts a little when you touch it.

For months, he circled back to that half-finished lyric. He’d hum the tune, rewrite a few lines, then close the notebook. Sometimes he’d just sit there, staring out the window, thinking about old roads, mistakes that never quite leave you, and the people you love in ways you can’t always explain.

Then came one quiet night.

After a long talk with one of his sons — the kind of talk that starts with jokes and ends with honesty — Merle walked back to the writing room. He didn’t warm up his voice. He didn’t flip through notebooks. He just sat down, held the guitar, and let whatever was still inside him come out.

His voice was rougher than before. Softer too.

But it carried something new — acceptance.

The song finally took shape.

Not perfect.

Not polished.

But real in a way only time and truth can shape.

He never played it for a crowd.

Never put it on an album.

He only performed it twice, both times in his living room, with no one listening except the walls that had heard every version of him.

After Merle passed, his family went through his things slowly, tenderly. In a small drawer, they found a handheld recorder. On it was the demo — raw, shaky, beautiful — labeled in Merle’s own handwriting:

“Finish this when I’m gone.”

Some songs are meant for the radio.

Some are meant for the world.

And some, like this one, are meant to be a quiet whisper from a man who spent his life turning truth into music.

Portable speakers

In many ways, the song was finished — not by rewrites or perfect chords, but by the man’s journey coming to rest. And when his family played it back, it wasn’t sadness they heard. It was Merle, one last time, telling the truth exactly as it lived in him.

It’s the kind of unfinished song that somehow says everything.