4t “Katharine Burr Blodgett: The Woman Who Made Glass Invisible and Broke Barriers”

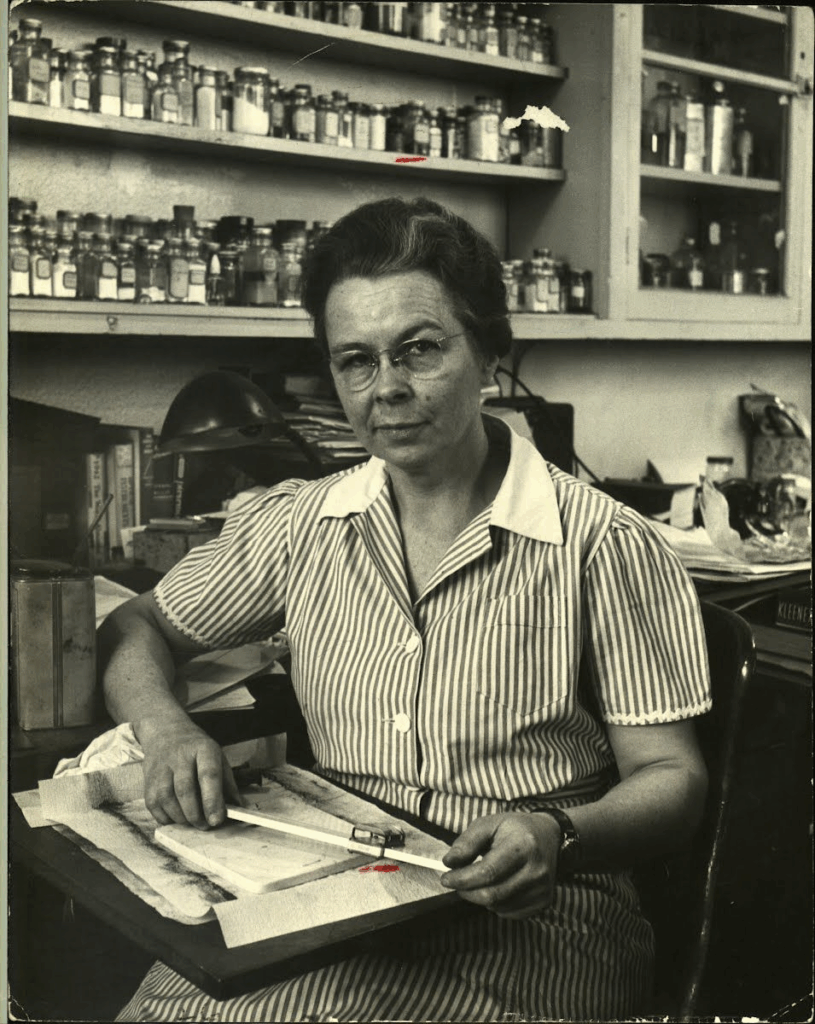

Katharine Burr Blodgett was a pioneering physicist whose groundbreaking inventions profoundly changed how we interact with everyday optical devices such as glasses, cameras, and smartphone screens. In 1917, at just 18 years old, she became the first woman ever hired at General Electric’s (GE) research laboratory in Schenectady, New York—a remarkable achievement considering the era’s gender biases, especially in science.

Born in 1898, just weeks after her father was tragically killed, Katharine was raised by a determined mother who ensured she received an exceptional education despite societal norms discouraging women from pursuing careers. Gifted in math and science, she graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a physics degree when female physicists were nearly unheard of.

Her early career took a defining turn when she was hired by Irving Langmuir, future Nobel laureate and head of GE’s research lab, who recognized her brilliance irrespective of gender. Following his encouragement, she earned a Ph.D. in physics from Cambridge University in 1926, becoming the first woman to do so at that institution.

Returning to GE, Katharine tackled a longstanding problem: light reflection on surfaces. Reflection caused glare and reduced the clarity of images through lenses—issues critical for cameras, eyeglasses, microscopes, telescopes, and cinema projectors. Katharine invented the revolutionary “non-reflective coating” by depositing ultra-thin layers of molecules on glass surfaces. These layers manipulated light waves, causing destructive interference that canceled out reflections. The result was virtually invisible glass with unprecedented clarity.

In 1938, her perfected coating was so effective that photographs showed what appeared to be empty space where the glass was—a testament to how she had made glass “invisible.” Her invention transformed optics, eliminating frustrating glare from eyeglasses and enhancing the sharpness of images in scientific instruments and film projection.

During World War II, her work became vital for military applications, improving submarine detection, aircraft de-icing, and smoke screens that saved lives. Over her career, she earned eight patents, and the Langmuir-Blodgett film deposition method she co-developed remains foundational in nanotechnology and materials science today.

Despite such monumental contributions, Katharine’s name was often overshadowed. Her male colleagues, including Langmuir who deservedly won the Nobel Prize, received much of the acclaim while her role was minimized. Public recognition of a brilliant woman in physics was rare and often met with surprise—reflecting a society unwilling to accept women’s achievements on equal footing.

Katharine never sought fame; her passion was clarity—scientific clarity and clearer vision for humanity. She dedicated 44 years to GE research until retiring in 1963, living modestly and unmarried, focused on her work.

Her legacy is everywhere: in anti-glare glasses, clear camera lenses, sharp microscope images, and vibrant cinema films. Every time we look through a screen or lens with reduced reflection, we benefit from her ingenuity. More importantly, she opened doors for women in physics and science, breaking barriers that created pathways for generations that followed.

History may have nearly made Katharine Burr Blodgett invisible, but today her story and contributions are finally brought into focus. She reminds us that brilliance knows no gender, and that every barrier broken lights the way forward for others.

Katharine Burr Blodgett made glass invisible—while history tried to erase her. Now, she is remembered, honored, and celebrated as a true pioneer who changed how humanity sees the world.