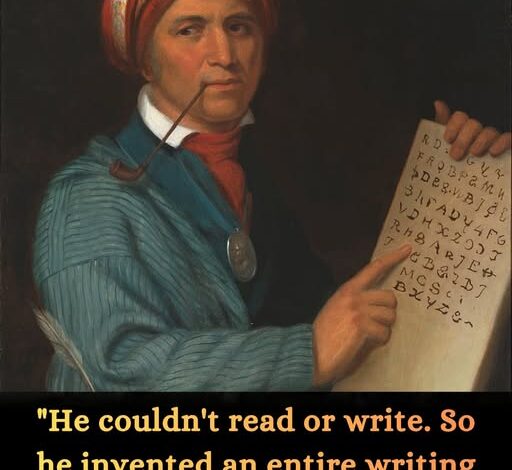

/10. He Couldn’t Read a Single Word—So He Invented a Writing System That Transformed a Nation

The Man Who Saw “Talking Leaves”

In the early 1800s, deep in the woodlands of what is now the southeastern United States, a Cherokee silversmith named Sequoyah watched white settlers carry papers covered in strange markings. They called them letters. Words. Documents. To Sequoyah, they seemed like magic—“talking leaves” that could speak across distance, across time, across generations.

The Cherokee Nation had no written language at the time. Their laws, history, and stories were carried in memory and shared by voice. As long as elders lived, their people’s knowledge lived with them. But Sequoyah saw danger: if knowledge existed only in memory, it could vanish with a single lost generation.

Something inside him refused to accept that fate.

A Dream the World Laughed At

Sequoyah became obsessed. If other people could trap language on paper, why couldn’t the Cherokee? His friends mocked him. His wife, tired of seeing him pour time into “nonsense,” reportedly burned his early attempts. Critics dismissed him—an illiterate craftsman with no formal education trying to do what scholars struggled to achieve.

But Sequoyah wasn’t deterred.

He had something no academic possessed:

an intuitive, internal understanding of the Cherokee language itself.

For twelve long years, he experimented. He tried symbols for words—too many. Pictographs—too vague. Systems borrowed from other languages—too mismatched. Anyone else would’ve given up. Instead, Sequoyah kept going.

Then came his breakthrough.

The Moment That Changed Everything

Sequoyah realized that Cherokee speech was built from repeating syllables, not individual letters like English. If he could assign a symbol to every syllable, he could capture the entire language in a finite set of characters.

He did the impossible.

He created 85 characters—just eighty-five—that could represent every sound in the Cherokee language.

It was elegant, simple, and astonishingly intuitive.

But convincing his people was another battle.

The Test That Silenced the Doubters

Cherokee leaders were skeptical. How could this strange system actually work?

Sequoyah staged a demonstration so brilliant it became legend.

He sat in one room. His daughter—who had learned the entire system in a matter of days—sat in another. The leaders dictated words. Sequoyah wrote them. His daughter read them aloud flawlessly, despite never hearing the original message.

The room fell silent.

This wasn’t a trick. It was proof.

The Cherokee had a written language.

A Nation Becomes Literate in Months

What happened next defies belief.

Within months—not years—thousands of Cherokee people learned to read and write using Sequoyah’s syllabary. Elders, farmers, leaders, children—everyone embraced it. Many mastering it faster than English speakers mastered their own alphabet.

By 1825, the Cherokee Nation had a literacy rate higher than that of many white American communities.

In 1828, they launched the Cherokee Phoenix—the first Native American newspaper—printed in both English and Cherokee. A full-scale written culture emerged almost overnight.

All because one man refused to let his language die.

A Miracle Born in the Darkest Times

It would be easy to believe this was a triumphal era for the Cherokee.

It wasn’t.

White settlers were pushing harder into Cherokee lands. The U.S. government was preparing to force the tribe westward. Pressure was mounting. Violence was growing. Removal was inevitable.

And yet, in the middle of this approaching tragedy, Sequoyah gave his people something priceless: a way to preserve their identity even if their homeland was taken.

A tool no government could outlaw.

No soldier could confiscate.

No distance could erase.

When the Trail of Tears began in 1838—when families were torn from their homes, when thousands died on the forced march west—the people carried Sequoyah’s syllabary with them.

They lost their land.

They lost loved ones.

But they did not lose their language.

The Writing System That Refused to Die

The Cherokee syllabary survived relocation. It survived government policies designed to erase Native culture. It survived the generational trauma of forced assimilation. It survived when countless Indigenous languages around the world did not.

Today, you’ll find Sequoyah’s characters on:

- Road signs across Cherokee Nation

- School textbooks

- Newspapers

- Official documents

- Digital keyboards

- Computer fonts

- And even texting apps

A silversmith from the 1800s—who never learned English, who never read a book, who never attended a single day of formal schooling—gave the Cherokee people a writing system that still thrives in the digital age.

How many people in history can say they invented an entire writing system… and watched a nation become literate because of it?

A Legacy Written in Fire and Memory

Sequoyah’s story isn’t just innovation. It is defiance.

It is resilience.

It is love made visible.

At a time when his people faced erasure, he created something immortal. And today, nearly two centuries later, Cherokee children still learn the very symbols he carved by hand.

Most writing systems evolved slowly over centuries.

Sequoyah created his in a cabin, alone.

Most require teams of scholars.

Sequoyah needed only his language and determination.

Most take generations to spread.

His took months.

Linguists call it one of the greatest intellectual achievements in human history. And yet, in popular culture, his name is barely known.

But maybe that’s changing now.

Because every time someone learns this story, the “talking leaves” he dreamed of keep speaking.